From Hopelessness, to the Hallways of Higher Education

A Chapter Adaptation from the Book Gumbo for the Soul III:

Males of Color Share Their Stories, Meditations, Affirmations, and Inspirations

Lawrence Scott, Ph.D.

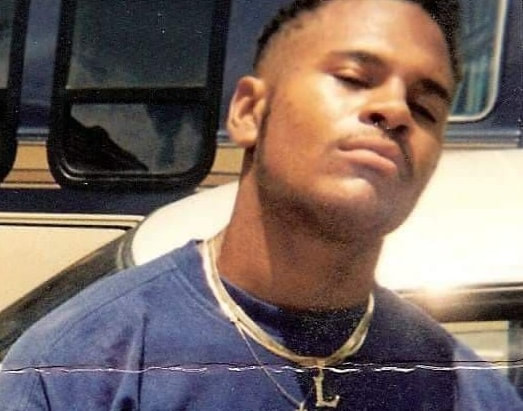

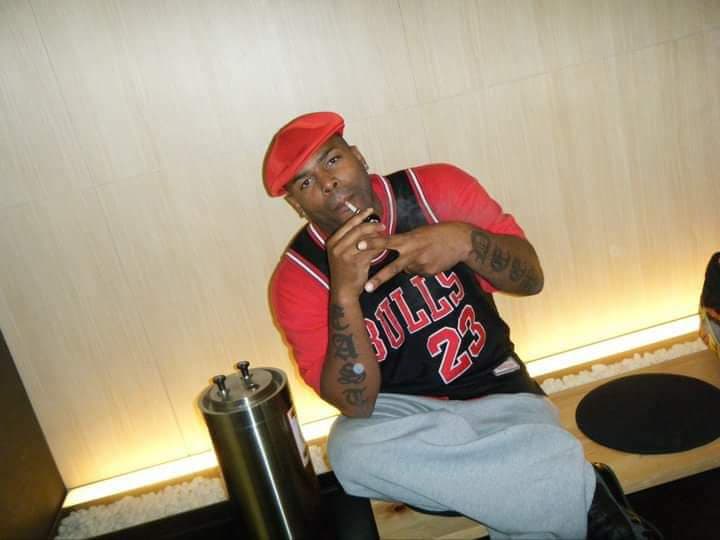

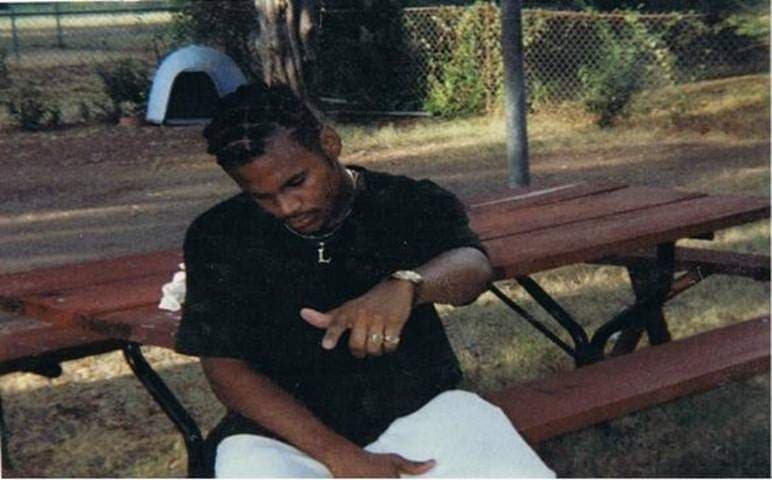

"Hey, Larry, Sho's dead." These were the chilling words uttered over the phone from my good friend Aaron regarding our childhood friend, Shomari Lewis, who was murdered on February 28, 2017. Many who knew us, knew that we were inseparable throughout middle and high school. In the past few years, I have lost five close friends and incessantly ask myself, "Why am I still here?". His death was inconceivable because many Black men who were murdered in America died before their 30's. Even though I have lost several friends throughout my life through the senseless, yet perpetual violence in my community, Shomari's untimely death crystallized my purpose to LIVE: To give hope to others who grew up poor, Black, with a mission to serve. The purpose of this submission is to illustrate how locating your purpose, developing an action plan, and persisting through the process, will solidify your desired success no matter the impediments.

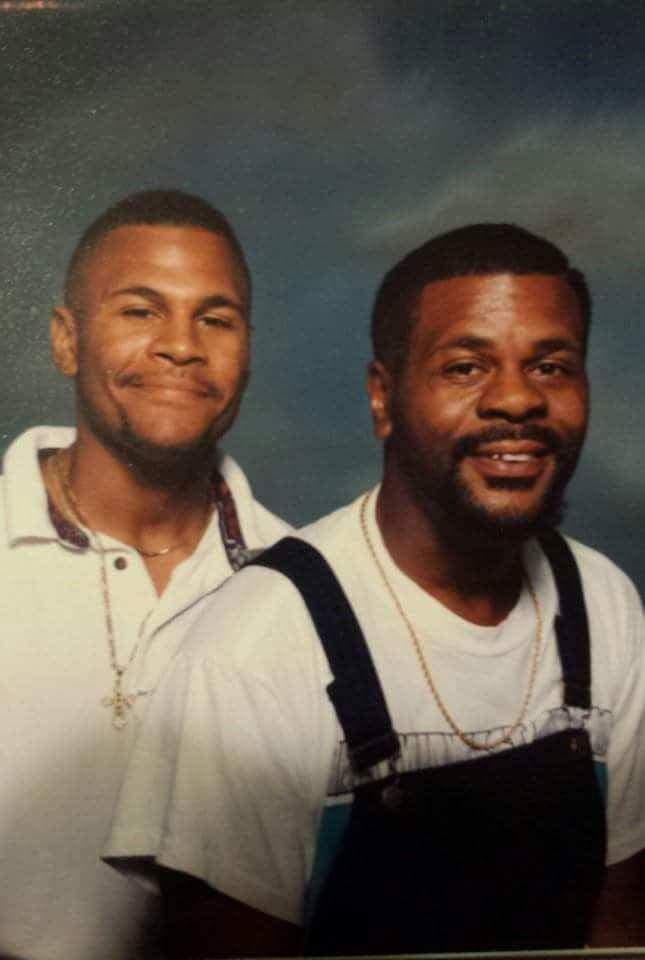

While in elementary, I lived a stable life. I was an "An Honor Roll" student, a part of a local church, Pop Warner football player, and a cub scout. In 4th grade, my parents divorced, and my life would change forever. During my middle school years, I would rotate schools between my mother's home in Charlotte, NC to my father's home in San Antonio, TX. This situation would take an abrupt halt during my 8th-grade year when several students were shot during a gang shootout at my feeder high school. My mom decided that she wanted me to attend a school called Victory Christian Center in Charlotte that focused on discipline, leadership, spirituality, and academics. This decision would be a lifesaver as my father sold drugs out of the home and eventually became addicted to crack cocaine. This school helped me understand my purpose in life, which was far beyond the current lifestyle of drinking 40oz bottles and selling drugs. Even back then I knew my purpose was to provide equitable opportunities of success for those who grew up like me.

Initially, when I arrived in Charlotte, my only plan was to survive. As a single mother, rearing two Black male teenagers, my mom did the best she could. Even though we had meager accommodations, I never felt underprivileged, or destitute. My mom always instilled thankfulness (to God) in all things, and to always serve others. We didn't have furniture, so we ate, watched T.V., and slept on the floor for about 8 months. I never stayed at home because my mother and older brother were always working as my older brother helped provide for the family. Once I came home, I would do my homework, then "go outside and play."

We lived in a duplex surrounded by drug dealers. It took me no time to start walking the streets and playing basketball with the neighborhood drug dealers. The major difference was that I was going to a predominately African American church school that taught leadership through spirituality. While there were a sparse amount of Black male mentors in San Antonio, at this school, half the staff were strong, family-oriented, mission-minded, Godly Black men whose goal was to reach young men like me. This exposure provided a counterbalance to ubiquitous archetypes of disreputable Black men I would see in my neighborhoods in San Antonio and Charlotte.

The paradigmatic shift occurred in high school when I met my English teacher and basketball coach, who would serve as one of the most influential persons in my life. Since my mom worked two jobs and she couldn't pick me up from school, Mr. Bego would take me home from basketball practice. He would talk to me about life, and how to envision and plan out strategies of success. This was the first time I encountered a family man that looked like me, had several degrees, and was published, with a love for God and a mission to serve students. During his classes, he would make us complete two-year, five-year, and ten-year goal sheets. He would guide us through introspective exercises that would anticipate obstacles. He knew that even the best plans will be tried by the fire of the process. Having Mr. Bego in my life gave me a roadmap to success, but didn't necessarily insulate me from extrinsic negative forces that would plague my latter high school and early college years.

In my senior year of high school, and going into college my audacious life plans were being created, but not devoid many obstacles. Most of those obstacles dealt with racial profiling. I was fired from a job that I had for over three years because some waitresses said I was stealing their tips. As a teenager, I experienced several instances dealing with law enforcement in which I feared for my life. Unfortunately, at the time, I didn't have the linguistic tools or social capital to address the disproportionate institutionalized marginalization and disempowerment that certain enforcement officers practiced.

Once, some friends and I were hanging out at an apartment complex after playing a few games of basketball. After about 20 minutes, around seven cop cars and ten cops came around the corner and ordered us on the ground. At the time, I didn't think anything of this since I knew we didn't do anything wrong. We were then handcuffed and placed on our knees as they searched us. After about 12 minutes of questioning and intermittent derogatory statements about the way we were dressed, we were released. When I asked them why they did this to us, one of the officers replied, "You fit the description of people who have been breaking into several apartments this week." I was devastated that this could happen in the land of the free. This systemic oppression began to crush my confidence and I started doubting my life's contribution. As I became older, I began to read about Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and others who were on a path of resistance and their resilience recalibrated their mission. My faith in God helped me persist beyond the resistance.

My freshman year in college, I was so happy that I was able to escape the malaise that plagued my teenage years. I was one of few African American males that lived on campus. One night as my friends and I were walking towards campus, one of the campus officers pulled us over. He checked our IDs and mentioned that we were stopped because we were jaywalking. After we proceeded to tell him we were students at the university, he ended this interaction with, "I got my eyes on you." Again, completely flabbergasted that even on a college campus this type of profiling existed. A month later, I decided to hang out with one of my friends, Mike from my old neighborhood. While arriving on campus, the police stopped us for failure to use the turn signal. We were ordered to get out of the car. This time, I knew I was going to jail because there were drugs, alcohol, and weapons in the car. They searched the car and found the contraband they were looking for the whole time. Being the man he was, Mike said:

"Larry, you are in college and doing something with your life. I will tell them that everything is mine and you were not aware of anything when you stepped in the car."

This sacrifice defined my perceived role in our friendship. Even though Mike was hauled off to jail, that night changed both of us forever. When he was released, he enlisted in the Marines and did a successful eight-year stint in the U.S. Marine Corp. He then started a lucrative job in the oil fields in Texas, became an international contractor and is doing well with his beautiful family. Since that day, we have intermittently kept in touch, as I thank him profusely for his sacrifice. We both knew that what he did that night ushered in a passion and purpose that was bigger than the both of us. Every time I give a speech, I talk about Mike and how his desire to make sure I pursued my dreams was another impetus to keep pushing for other young Black boys that are facing their giants. Despite the other hardships, such as a stint of homelessness and having to live with my Pastors, Keith and Denetrice Graham, I was able to finish my Bachelor's and Master's degrees, and ultimately pursue my Ph.D.

Doctoral Process - An Exercise of Purpose

After I finished my Master's, some of the best advice I received, was to not stop my education but to keep going. Even though at the time, pursuing a Ph.D. was inconvenient, I knew it was a part of a bigger plan to fulfill my purpose on the earth. In retrospect, this was one of the best decisions I've made in my life.

When I first started the Ph.D. program, I was immediately made aware of the sparse number of African Americans, and an even smaller number of African American men in my program. With a class of 32, there was only one other African American male, and one African American female. I was the only African American in most of my classes. This disparity was the impetus I needed to begin research in African American male academic attainment. There were also anecdotal occurrences that solidified the need to pursue a doctoral degree. I have been in the educational sector as a teacher and as a coach and I was now working as a guidance counselor for over 11 years. I had become tired of seeing our African American kids under perform, even though they received the same instruction as their White and Hispanic counterparts. I knew that there were non-cognitive factors, such as cultural ethos, socio-economic, equal access to early childhood education that could play a factor in the educational attainment of African American men.

I had great professors and advisors who guided me through the process to make sure that my research was representative of my mission. One professor, Dr. Jessica Kimmel, would always talk to me about the need to make a difference by gathering candid stories of successful African American men. Some experiences illustrated that there was still a need to discuss African American equity, and my research could be a catalyst to change misperceptions. I can vividly recall a time when one of the professors asked me whether I was coming to pick up the trash out of her classroom as if I was a janitor. She exclaimed, "You can start in my room, there is a lot of trash in there." To her dismay and embarrassment, I told her I was taking her class as a doctoral student. I knew that my role as a doctoral student went far beyond the confines of studying or writing research, but becoming an example of Black male intellectualism to counterbalance the ubiquitous anti-intellectualism that has plagued my community for generations. I knew that my time was limited; that something must be done and I was up for the challenge to change the educational outcome in my family lineage for generations to come.

You Are Created To Serve:

Getting a doctoral degree as a Black man in America is meaningless unless you are leveraging your social capital to GIVE BACK. Living by the purpose, plan, and process principles has helped me give back in ways unimaginable. Now as an assistant professor in Educational Leadership at a four-year University and an executive director over a non-profit which has given over half a million dollars in scholarships since its inception, I can now be a role model for and conduit to successful outcomes for others who grew up like me. To start your journey of finding your purpose, you must ask this basic, but complex question: "Why are you here?". God created you for a reason! Once you have established your "Why," create a plan that is measurable, dated, specific, and feasible. For instance, a statement in my plan said, "By Fall of 2001, I will secure a job as a teacher in San Antonio ISD, and begin my Master's degree in Counseling."

Lastly, you have to understand that achieving your goals is a process. You will experience many hardships, but take solace in knowing that this is all a part of the process. Build momentum by celebrating the small victories with those who helped you succeed. A series of small victories lead to a victorious life. Also, find mentors who have achieved your desired goals, and make them a significant part of your social network and cadre of counselors. Mentors will help you stay cognizant that trials are temporal, and will only improve your story of resilience. Furthermore, to win in life put yourself in uncomfortable situations that will force you to grow (disequilibrium). For me, that was vying for leadership positions throughout high school and college. Finally, and most importantly, to win in this life, never give up! I vividly recall asking my girlfriend to marry me on the Eiffel Tower in Paris, and her saying no. She said yes seven months later and we have been married for over 15 years. Plans may change, but your purpose will remain the same, despite incessant rejection. Never giving up, my dad has assumed his role of my father and he is an amazing grandfather to our children. Living with these principles of finding my purpose, creating a plan of action, and going through the process helped me transition from being hopeless in the hood, to navigating the hallways of higher learning and allowing me to give back in ways I could have never imagined. Now, my friend's death gives me an understanding that we need to inspire our brothers and sisters to LIVE a mission-minded LIFE, by being an intergenerational positive difference-maker.

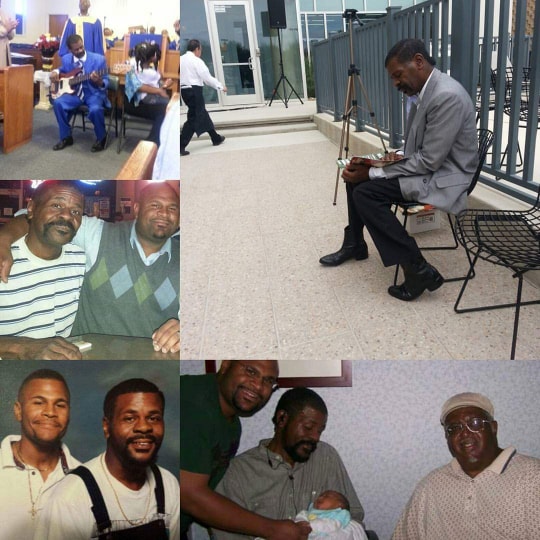

This submission is dedicated to the family and friends who have passed on, but who have shaped my desire to make an intergeneration impact: My Grandparents, Johnnie, and Willie Scott, Joshua Vargas, Demontre Pamilton, Larry "Coach" Woods, and of course, my childhood friend, Shomari Lewis. You are forever missed.

While in elementary, I lived a stable life. I was an "An Honor Roll" student, a part of a local church, Pop Warner football player, and a cub scout. In 4th grade, my parents divorced, and my life would change forever. During my middle school years, I would rotate schools between my mother's home in Charlotte, NC to my father's home in San Antonio, TX. This situation would take an abrupt halt during my 8th-grade year when several students were shot during a gang shootout at my feeder high school. My mom decided that she wanted me to attend a school called Victory Christian Center in Charlotte that focused on discipline, leadership, spirituality, and academics. This decision would be a lifesaver as my father sold drugs out of the home and eventually became addicted to crack cocaine. This school helped me understand my purpose in life, which was far beyond the current lifestyle of drinking 40oz bottles and selling drugs. Even back then I knew my purpose was to provide equitable opportunities of success for those who grew up like me.

Initially, when I arrived in Charlotte, my only plan was to survive. As a single mother, rearing two Black male teenagers, my mom did the best she could. Even though we had meager accommodations, I never felt underprivileged, or destitute. My mom always instilled thankfulness (to God) in all things, and to always serve others. We didn't have furniture, so we ate, watched T.V., and slept on the floor for about 8 months. I never stayed at home because my mother and older brother were always working as my older brother helped provide for the family. Once I came home, I would do my homework, then "go outside and play."

We lived in a duplex surrounded by drug dealers. It took me no time to start walking the streets and playing basketball with the neighborhood drug dealers. The major difference was that I was going to a predominately African American church school that taught leadership through spirituality. While there were a sparse amount of Black male mentors in San Antonio, at this school, half the staff were strong, family-oriented, mission-minded, Godly Black men whose goal was to reach young men like me. This exposure provided a counterbalance to ubiquitous archetypes of disreputable Black men I would see in my neighborhoods in San Antonio and Charlotte.

The paradigmatic shift occurred in high school when I met my English teacher and basketball coach, who would serve as one of the most influential persons in my life. Since my mom worked two jobs and she couldn't pick me up from school, Mr. Bego would take me home from basketball practice. He would talk to me about life, and how to envision and plan out strategies of success. This was the first time I encountered a family man that looked like me, had several degrees, and was published, with a love for God and a mission to serve students. During his classes, he would make us complete two-year, five-year, and ten-year goal sheets. He would guide us through introspective exercises that would anticipate obstacles. He knew that even the best plans will be tried by the fire of the process. Having Mr. Bego in my life gave me a roadmap to success, but didn't necessarily insulate me from extrinsic negative forces that would plague my latter high school and early college years.

In my senior year of high school, and going into college my audacious life plans were being created, but not devoid many obstacles. Most of those obstacles dealt with racial profiling. I was fired from a job that I had for over three years because some waitresses said I was stealing their tips. As a teenager, I experienced several instances dealing with law enforcement in which I feared for my life. Unfortunately, at the time, I didn't have the linguistic tools or social capital to address the disproportionate institutionalized marginalization and disempowerment that certain enforcement officers practiced.

Once, some friends and I were hanging out at an apartment complex after playing a few games of basketball. After about 20 minutes, around seven cop cars and ten cops came around the corner and ordered us on the ground. At the time, I didn't think anything of this since I knew we didn't do anything wrong. We were then handcuffed and placed on our knees as they searched us. After about 12 minutes of questioning and intermittent derogatory statements about the way we were dressed, we were released. When I asked them why they did this to us, one of the officers replied, "You fit the description of people who have been breaking into several apartments this week." I was devastated that this could happen in the land of the free. This systemic oppression began to crush my confidence and I started doubting my life's contribution. As I became older, I began to read about Martin Luther King, Malcolm X, and others who were on a path of resistance and their resilience recalibrated their mission. My faith in God helped me persist beyond the resistance.

My freshman year in college, I was so happy that I was able to escape the malaise that plagued my teenage years. I was one of few African American males that lived on campus. One night as my friends and I were walking towards campus, one of the campus officers pulled us over. He checked our IDs and mentioned that we were stopped because we were jaywalking. After we proceeded to tell him we were students at the university, he ended this interaction with, "I got my eyes on you." Again, completely flabbergasted that even on a college campus this type of profiling existed. A month later, I decided to hang out with one of my friends, Mike from my old neighborhood. While arriving on campus, the police stopped us for failure to use the turn signal. We were ordered to get out of the car. This time, I knew I was going to jail because there were drugs, alcohol, and weapons in the car. They searched the car and found the contraband they were looking for the whole time. Being the man he was, Mike said:

"Larry, you are in college and doing something with your life. I will tell them that everything is mine and you were not aware of anything when you stepped in the car."

This sacrifice defined my perceived role in our friendship. Even though Mike was hauled off to jail, that night changed both of us forever. When he was released, he enlisted in the Marines and did a successful eight-year stint in the U.S. Marine Corp. He then started a lucrative job in the oil fields in Texas, became an international contractor and is doing well with his beautiful family. Since that day, we have intermittently kept in touch, as I thank him profusely for his sacrifice. We both knew that what he did that night ushered in a passion and purpose that was bigger than the both of us. Every time I give a speech, I talk about Mike and how his desire to make sure I pursued my dreams was another impetus to keep pushing for other young Black boys that are facing their giants. Despite the other hardships, such as a stint of homelessness and having to live with my Pastors, Keith and Denetrice Graham, I was able to finish my Bachelor's and Master's degrees, and ultimately pursue my Ph.D.

Doctoral Process - An Exercise of Purpose

After I finished my Master's, some of the best advice I received, was to not stop my education but to keep going. Even though at the time, pursuing a Ph.D. was inconvenient, I knew it was a part of a bigger plan to fulfill my purpose on the earth. In retrospect, this was one of the best decisions I've made in my life.

When I first started the Ph.D. program, I was immediately made aware of the sparse number of African Americans, and an even smaller number of African American men in my program. With a class of 32, there was only one other African American male, and one African American female. I was the only African American in most of my classes. This disparity was the impetus I needed to begin research in African American male academic attainment. There were also anecdotal occurrences that solidified the need to pursue a doctoral degree. I have been in the educational sector as a teacher and as a coach and I was now working as a guidance counselor for over 11 years. I had become tired of seeing our African American kids under perform, even though they received the same instruction as their White and Hispanic counterparts. I knew that there were non-cognitive factors, such as cultural ethos, socio-economic, equal access to early childhood education that could play a factor in the educational attainment of African American men.

I had great professors and advisors who guided me through the process to make sure that my research was representative of my mission. One professor, Dr. Jessica Kimmel, would always talk to me about the need to make a difference by gathering candid stories of successful African American men. Some experiences illustrated that there was still a need to discuss African American equity, and my research could be a catalyst to change misperceptions. I can vividly recall a time when one of the professors asked me whether I was coming to pick up the trash out of her classroom as if I was a janitor. She exclaimed, "You can start in my room, there is a lot of trash in there." To her dismay and embarrassment, I told her I was taking her class as a doctoral student. I knew that my role as a doctoral student went far beyond the confines of studying or writing research, but becoming an example of Black male intellectualism to counterbalance the ubiquitous anti-intellectualism that has plagued my community for generations. I knew that my time was limited; that something must be done and I was up for the challenge to change the educational outcome in my family lineage for generations to come.

You Are Created To Serve:

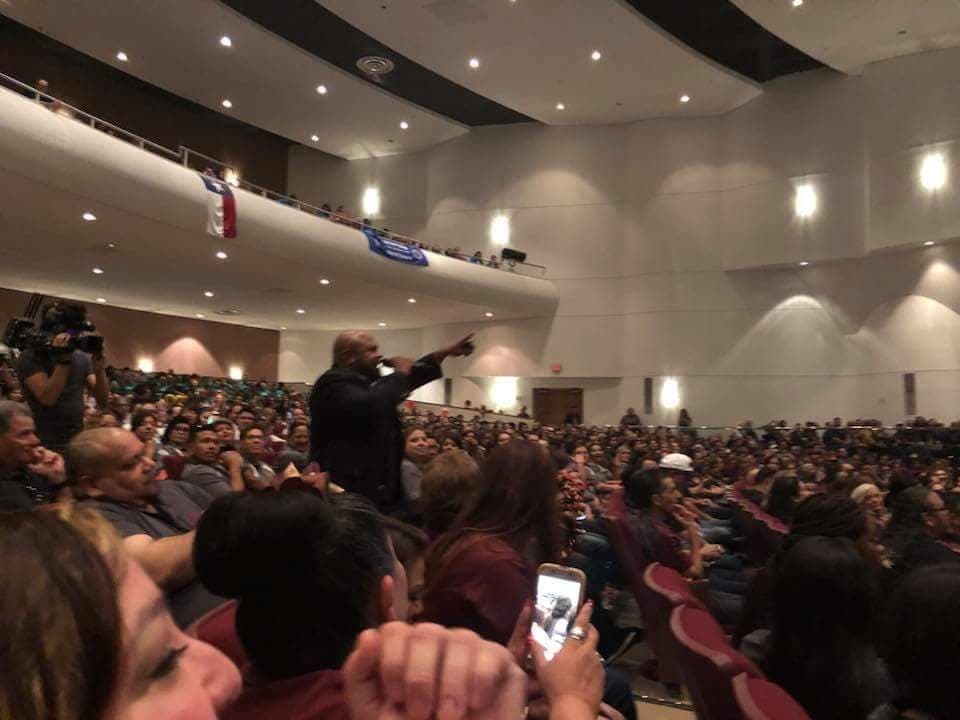

Getting a doctoral degree as a Black man in America is meaningless unless you are leveraging your social capital to GIVE BACK. Living by the purpose, plan, and process principles has helped me give back in ways unimaginable. Now as an assistant professor in Educational Leadership at a four-year University and an executive director over a non-profit which has given over half a million dollars in scholarships since its inception, I can now be a role model for and conduit to successful outcomes for others who grew up like me. To start your journey of finding your purpose, you must ask this basic, but complex question: "Why are you here?". God created you for a reason! Once you have established your "Why," create a plan that is measurable, dated, specific, and feasible. For instance, a statement in my plan said, "By Fall of 2001, I will secure a job as a teacher in San Antonio ISD, and begin my Master's degree in Counseling."

Lastly, you have to understand that achieving your goals is a process. You will experience many hardships, but take solace in knowing that this is all a part of the process. Build momentum by celebrating the small victories with those who helped you succeed. A series of small victories lead to a victorious life. Also, find mentors who have achieved your desired goals, and make them a significant part of your social network and cadre of counselors. Mentors will help you stay cognizant that trials are temporal, and will only improve your story of resilience. Furthermore, to win in life put yourself in uncomfortable situations that will force you to grow (disequilibrium). For me, that was vying for leadership positions throughout high school and college. Finally, and most importantly, to win in this life, never give up! I vividly recall asking my girlfriend to marry me on the Eiffel Tower in Paris, and her saying no. She said yes seven months later and we have been married for over 15 years. Plans may change, but your purpose will remain the same, despite incessant rejection. Never giving up, my dad has assumed his role of my father and he is an amazing grandfather to our children. Living with these principles of finding my purpose, creating a plan of action, and going through the process helped me transition from being hopeless in the hood, to navigating the hallways of higher learning and allowing me to give back in ways I could have never imagined. Now, my friend's death gives me an understanding that we need to inspire our brothers and sisters to LIVE a mission-minded LIFE, by being an intergenerational positive difference-maker.

This submission is dedicated to the family and friends who have passed on, but who have shaped my desire to make an intergeneration impact: My Grandparents, Johnnie, and Willie Scott, Joshua Vargas, Demontre Pamilton, Larry "Coach" Woods, and of course, my childhood friend, Shomari Lewis. You are forever missed.

Chronicles of a Scholar

From Hopelessness, to the Hallways of Higher Education

From Hopelessness, to the Hallways of Higher Education

Dr. Lawrence Scott

Professor and Researcher

Texas A&M University-San Antonio

Dr. Lawrence Scott currently is an Assistant Professor at Texas A&M University-San Antonio. He is also the Executive Director of the Community for Life Foundation, a non-profit that has given over half million dollars in scholarships to more than 200 recipients nationwide, has fed over 1,700 families since the inception of its annual O’Give Thanks Initiative, and holds annual career and college readiness sessions. Prior to teaching in higher education, Dr. Scott served over 16 years in the P-12 sector as a secondary teacher, athletics coach, guidance counselor, district-level curriculum specialist, and secondary administrator all in San Antonio ISD. Dr. Scott began S.E.N.D. Consulting, which he has given trainings for many universities, school districts, churches and organizations such as Teach for America, SA Youth, Catholic Charities and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

He has won numerous awards: San Antonio Business Journal’s 2018 Man of the Year. Golden Key International Honor Society Educational Leadership Award-University of the Incarnate Word, Teach For America Leadership Inspiration Award, Phi Delta Kappa Educator’s Hall of Fame, San Antonio ISD Foundation Innovative Educator of the Year, Presidential Award Recipient-St. Mary’s University.

"He is a member of Now Word Covenant Church. He lives with his wife Chiara, and his kids Gabriella and Christian."

EDUCATION CREDENTIALS:

"He is a member of Now Word Covenant Church. He lives with his wife Chiara, and his kids Gabriella and Christian."

Email: [email protected]

He has won numerous awards: San Antonio Business Journal’s 2018 Man of the Year. Golden Key International Honor Society Educational Leadership Award-University of the Incarnate Word, Teach For America Leadership Inspiration Award, Phi Delta Kappa Educator’s Hall of Fame, San Antonio ISD Foundation Innovative Educator of the Year, Presidential Award Recipient-St. Mary’s University.

"He is a member of Now Word Covenant Church. He lives with his wife Chiara, and his kids Gabriella and Christian."

EDUCATION CREDENTIALS:

- Ph.D. in Organizational Leadership, University of the Incarnate Word

- M.A. in Educational Psychology/Counseling, University of Texas at San Antonio

- B.A. in Political Science/History, St. Mary’s University

"He is a member of Now Word Covenant Church. He lives with his wife Chiara, and his kids Gabriella and Christian."

Email: [email protected]