Dr. Tommy J. Curry @DrTJC

Responds to Facebook Questions about His Book Man-Not

@DrTJC

@DrTJC

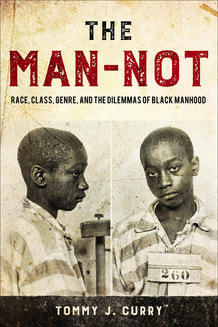

Facebook: You have George Stinney on your cover. As you know George Stinney was a poor, black boy wrongfully convicted and executed for the murder of 2 white girls. In South Carolina in 1944. Your book Man-Not is about black men being victimized in this country. While George Stinney was a victim of racism and prejudice of the black male, I find the execution of George Stinney child abuse and having George Stinney’s child image on your book cover is victimizing him all over again. Unless your book examines solely the case of George Stinney I another image would have been more appropriate to you very important book. Can you speak to the decision of using George Stinney image as your book cover?

Dr. Tommy J. Curry: I chose George Stinney Jr. for a couple of reasons for the cover of my book. As I argue in chapter 1, the idea of Black males as rapists started post-emancipation. The argument of white ethnologists and suffragettes alike was that the Black male was a threat to the womanhood of the white race and need to be exterminated to ensure the survival of the white republic. Specifically at the turn of the 20th century, white sexologists like William Lee Howard argued that at puberty all mental development of the Black male ceases and he becomes a rapist. George Stinney Jr. was an innocent victim of this ethnological thinking in the 1940s. In chapter 5 of my book I analyze his murder and the false accusation of rape against him as part of the threat society constructs Black males as. In my mind, Stinney is the perfect example of The Man-Not that I am speaking about throughout my book--a boy, a child, framed and seen by this society as a rapist despite the impossibility of him committing such an act. Furthermore, I document how the court had evidence clearing Mr. Stinney Jr. of the crime and choose not to reveal it to the jury. This is an example of what I call characterological defect and the burden that all Black men suffer in racist patriarchal societies. What I am suggesting to Black men in presenting Mr. Stinney Jr. to the world is that the world does not see us as boys, will not recognize us as men, but will only see us as the rapist and in need of death to protect the order of society.

Facebook: Have you found it difficult to present Black men as victims, especially within the Black community? And what are some examples of those challenges?

Dr. Tommy J. Curry: I think there is more resistance presenting Black males as victims amongst Black academics than the Black community. I often receive letters of support from Black men who are survivors of rape and domestic violence, or Black men suffering from disability or trauma, as well as Black mothers. In the academy, Black masculinity is understood under one lens, namely Black feminism. Black males do not have the kinds of debates or the variety of theories that we find in Masculinities Studies that deal with white males in the United States and Europe. There is no delineation between hegemonic and non-hegemonic masculinity for Black men. You are either feminist or you are not. In (white) masculinities studies, you have plural masculinities (Abiom), protest masculinities (Messerschmidt), hybrid masculinities (Bridges & Pascoe), and all of these have some sort of ethnography attached to their theorization. This is not the case for Black males. We often rely on outdated concepts of masculinity theory like hegemonic and toxic masculinity and present them as beyond contestation.

I guess the clearest example of this is in how we interpret disproportionate rates of intimate partner violence (IPV) in the Black community. For example, the assumptions of many Black feminist authors such as Kimberle Crenshaw or bell hooks follow the Duluth model of domestic abuse. The Duluth model asserts that men in a patriarchal society abuse for power and control of women. This was the dominant theory concerning IPV in the 1980s and into the early 2000s. However amongst Blacks there has always been a history of bidirectional violence and disproportionate rates of Black males as victims of spousal homicide in the literature. Now back in the 1930s, the predominant view of Negro race was that Black men and women killed each other because of infidelity. Black men were unfaithful and Black women were jealous, so according to John Dollard and various white sociologists, the hyper-sexuality of the Negro and primitive familial unit meant that Black men and women used violence to curtail infidelity. In the 1980s, white feminists gave Black scholars a new theory based on patriarchy and then Black men became the culprits. In the post-Duluth or what Michael P. Johnson called the post-patriarchal era of research, ecological causes of IPV are being investigated. Linda Mills for example theorizes child physical and sexual abuse is linked to IPV more than sexist attitudes and that in white populations there is a gender symmetry that becomes apparent. Epidemiologists like Raul Caetano have been looking at IPV and bidirectionality for several decades focusing on alcoholism, poverty, and social stigma. Unfortunately, none of this empirical research for the last 20 years has affected the way we theorize about Black men and women or families. Despite one of the founders of the Duluth model admitting it was made up with no clinical evidence and theorized based on jingles, this is the dominant view of IPV amongst Black scholars.

In the academy, there is an unwritten rule that we cannot analyze female violence or perpetration. This idea makes it difficult for some people to accept the stories of Black male victims of domestic abuse or child sexual abuse. I think the first response to doing this kind of work is that it is misogynist because it implicates Black women in communal violence, and because it contradicts many of the assumptions Black feminist theory uses to interpret Black men as patriarchs.

As I mentioned in my interview with Dr. Mike Robinson of Forest Of The Rain Productions, there is a resistance to seeing the sexual victimization of Black men in society more generally. I analyze the links between the rape of Black men and boys during slavery and the rape of Black male by white vigilantes and the police. This research is uncomfortable to begin with, but on top of that we have this identity politics regarding Black men that aims to censor research exploring the various sexual violence that Black males have enduring throughout history. In the book I recount being boo-ed by a Black feminist who said studying the rape of Black men during slavery erases Black women. Within this logic, any work that centers Black males as victims is misogynistic. I tend not to view such a charge seriously since the exploration of Black male victims historically and in our everyday lives is more important to me. We have Black men and boys who are hurt, abused, and raped by Black women in their lives. We have Black men and boys who are also hurt, abused, and raped by other Black men in their lives as well. I tend to side with victims in this regard.

Facebook: What are your White male colleagues saying about your study? Are you getting support from them?

Dr. Tommy J. Curry: I think white men do not really know what to think about my work on white masculinity and patriarchy because it focuses on the relationship dominant group males have to subordinate male targets following Jim Sidanius and Errol Miller’s research. Given that I use social dominance theory, theories rooted in Global South Masculinity studies and various case studies in gendercide, I think white men are uncomfortable with the idea that I argue that what is assumed to a heterosexual urge to protect white endogamy through the killing of racialized males in patriarchal societies is actual homoerotic. Amongst race theorists, this argument seems strange because we do not study Black males as victims of patriarchy, but when I bring up this argument concerning the rape of Jewish or Armenian men and boys during their respective genocides this does not draw any suspicions. I think this is because there has been much more openness to the historical record which involves the rape of men and boys as well as women in genocide studies, whereas race theory in the United States primarily focuses on Black-white race relations and isolates its study of men and boys to feminist interpretations of masculinity. Consequently, there is not as much of a focus on the violence males suffer under repressive regimes but on their alleged privilege as patriarchal men. That is a long way of saying that many of my white male colleagues do not engage the relationship between white masculinity and sexual violence against Black men and boys, but some of my white male colleagues are interested in this argument when it focuses on Jewish boys raped by German SS or the rape of Armenian men by Turkish soldiers.

To hear Dr. Mike Robinson's interviews with Dr. Tommy J. Curry click the links below:

Dr. Tommy J. Curry Enters the Author's Corner

Unplugged with Dr. Tommy J. Curry

Dr. Tommy J. Curry: I chose George Stinney Jr. for a couple of reasons for the cover of my book. As I argue in chapter 1, the idea of Black males as rapists started post-emancipation. The argument of white ethnologists and suffragettes alike was that the Black male was a threat to the womanhood of the white race and need to be exterminated to ensure the survival of the white republic. Specifically at the turn of the 20th century, white sexologists like William Lee Howard argued that at puberty all mental development of the Black male ceases and he becomes a rapist. George Stinney Jr. was an innocent victim of this ethnological thinking in the 1940s. In chapter 5 of my book I analyze his murder and the false accusation of rape against him as part of the threat society constructs Black males as. In my mind, Stinney is the perfect example of The Man-Not that I am speaking about throughout my book--a boy, a child, framed and seen by this society as a rapist despite the impossibility of him committing such an act. Furthermore, I document how the court had evidence clearing Mr. Stinney Jr. of the crime and choose not to reveal it to the jury. This is an example of what I call characterological defect and the burden that all Black men suffer in racist patriarchal societies. What I am suggesting to Black men in presenting Mr. Stinney Jr. to the world is that the world does not see us as boys, will not recognize us as men, but will only see us as the rapist and in need of death to protect the order of society.

Facebook: Have you found it difficult to present Black men as victims, especially within the Black community? And what are some examples of those challenges?

Dr. Tommy J. Curry: I think there is more resistance presenting Black males as victims amongst Black academics than the Black community. I often receive letters of support from Black men who are survivors of rape and domestic violence, or Black men suffering from disability or trauma, as well as Black mothers. In the academy, Black masculinity is understood under one lens, namely Black feminism. Black males do not have the kinds of debates or the variety of theories that we find in Masculinities Studies that deal with white males in the United States and Europe. There is no delineation between hegemonic and non-hegemonic masculinity for Black men. You are either feminist or you are not. In (white) masculinities studies, you have plural masculinities (Abiom), protest masculinities (Messerschmidt), hybrid masculinities (Bridges & Pascoe), and all of these have some sort of ethnography attached to their theorization. This is not the case for Black males. We often rely on outdated concepts of masculinity theory like hegemonic and toxic masculinity and present them as beyond contestation.

I guess the clearest example of this is in how we interpret disproportionate rates of intimate partner violence (IPV) in the Black community. For example, the assumptions of many Black feminist authors such as Kimberle Crenshaw or bell hooks follow the Duluth model of domestic abuse. The Duluth model asserts that men in a patriarchal society abuse for power and control of women. This was the dominant theory concerning IPV in the 1980s and into the early 2000s. However amongst Blacks there has always been a history of bidirectional violence and disproportionate rates of Black males as victims of spousal homicide in the literature. Now back in the 1930s, the predominant view of Negro race was that Black men and women killed each other because of infidelity. Black men were unfaithful and Black women were jealous, so according to John Dollard and various white sociologists, the hyper-sexuality of the Negro and primitive familial unit meant that Black men and women used violence to curtail infidelity. In the 1980s, white feminists gave Black scholars a new theory based on patriarchy and then Black men became the culprits. In the post-Duluth or what Michael P. Johnson called the post-patriarchal era of research, ecological causes of IPV are being investigated. Linda Mills for example theorizes child physical and sexual abuse is linked to IPV more than sexist attitudes and that in white populations there is a gender symmetry that becomes apparent. Epidemiologists like Raul Caetano have been looking at IPV and bidirectionality for several decades focusing on alcoholism, poverty, and social stigma. Unfortunately, none of this empirical research for the last 20 years has affected the way we theorize about Black men and women or families. Despite one of the founders of the Duluth model admitting it was made up with no clinical evidence and theorized based on jingles, this is the dominant view of IPV amongst Black scholars.

In the academy, there is an unwritten rule that we cannot analyze female violence or perpetration. This idea makes it difficult for some people to accept the stories of Black male victims of domestic abuse or child sexual abuse. I think the first response to doing this kind of work is that it is misogynist because it implicates Black women in communal violence, and because it contradicts many of the assumptions Black feminist theory uses to interpret Black men as patriarchs.

As I mentioned in my interview with Dr. Mike Robinson of Forest Of The Rain Productions, there is a resistance to seeing the sexual victimization of Black men in society more generally. I analyze the links between the rape of Black men and boys during slavery and the rape of Black male by white vigilantes and the police. This research is uncomfortable to begin with, but on top of that we have this identity politics regarding Black men that aims to censor research exploring the various sexual violence that Black males have enduring throughout history. In the book I recount being boo-ed by a Black feminist who said studying the rape of Black men during slavery erases Black women. Within this logic, any work that centers Black males as victims is misogynistic. I tend not to view such a charge seriously since the exploration of Black male victims historically and in our everyday lives is more important to me. We have Black men and boys who are hurt, abused, and raped by Black women in their lives. We have Black men and boys who are also hurt, abused, and raped by other Black men in their lives as well. I tend to side with victims in this regard.

Facebook: What are your White male colleagues saying about your study? Are you getting support from them?

Dr. Tommy J. Curry: I think white men do not really know what to think about my work on white masculinity and patriarchy because it focuses on the relationship dominant group males have to subordinate male targets following Jim Sidanius and Errol Miller’s research. Given that I use social dominance theory, theories rooted in Global South Masculinity studies and various case studies in gendercide, I think white men are uncomfortable with the idea that I argue that what is assumed to a heterosexual urge to protect white endogamy through the killing of racialized males in patriarchal societies is actual homoerotic. Amongst race theorists, this argument seems strange because we do not study Black males as victims of patriarchy, but when I bring up this argument concerning the rape of Jewish or Armenian men and boys during their respective genocides this does not draw any suspicions. I think this is because there has been much more openness to the historical record which involves the rape of men and boys as well as women in genocide studies, whereas race theory in the United States primarily focuses on Black-white race relations and isolates its study of men and boys to feminist interpretations of masculinity. Consequently, there is not as much of a focus on the violence males suffer under repressive regimes but on their alleged privilege as patriarchal men. That is a long way of saying that many of my white male colleagues do not engage the relationship between white masculinity and sexual violence against Black men and boys, but some of my white male colleagues are interested in this argument when it focuses on Jewish boys raped by German SS or the rape of Armenian men by Turkish soldiers.

To hear Dr. Mike Robinson's interviews with Dr. Tommy J. Curry click the links below:

Dr. Tommy J. Curry Enters the Author's Corner

Unplugged with Dr. Tommy J. Curry